“Art enables us to find ourselves + lose ourselves at the same time.”

Glenn Loughrey has designed a series of glass panels for the narthex screen, or cathedral entrance, depicting the traditional lands on which the cathedral stands. >> Read more in the article by ABC News here <<

The story of Australia is a story told from the edges. It is a story that often leaves out important bits such as Tasmania, the deep north or the red centre and ignores the darker stroies at the heart of the countries history. It is a story ignoring the story of the people who have lived here for some 50,000 years. There is much more to Australia than a story told from the perimeter.

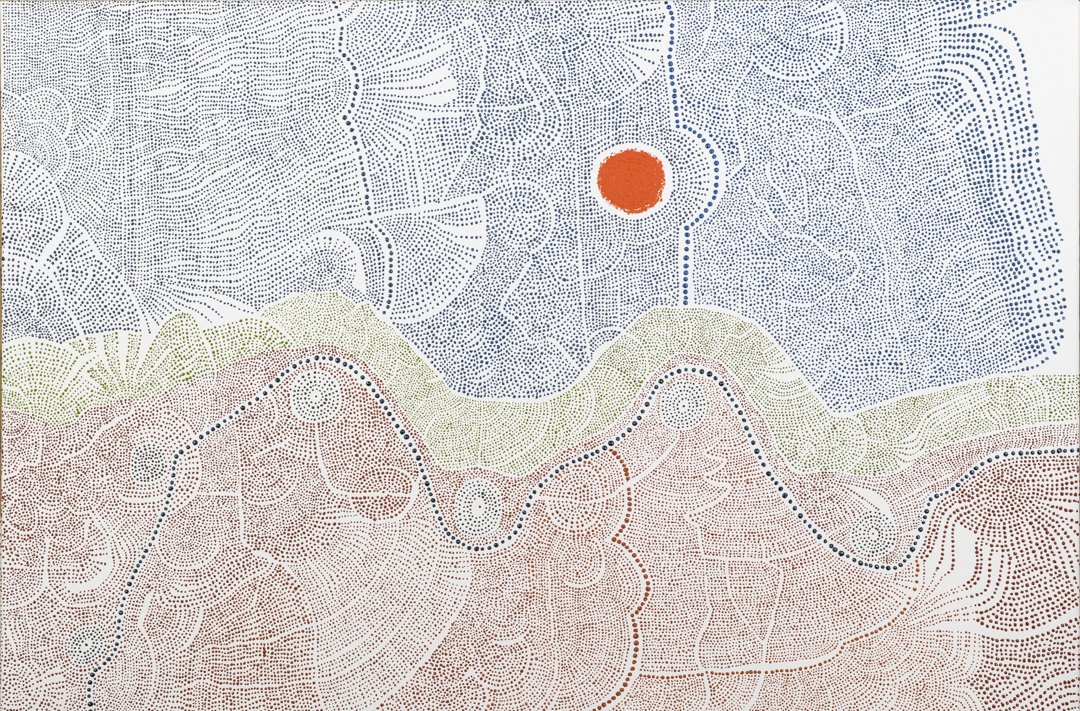

Indigenous people are indistinguishable from their country. This picture portrays the authors country around Ulan on the Goulburn river in NSW Australia. The painting was painted from memory, as almost all of the country described has been destroyed by three open cut coal mines, and does not exist as it did in my childhood.

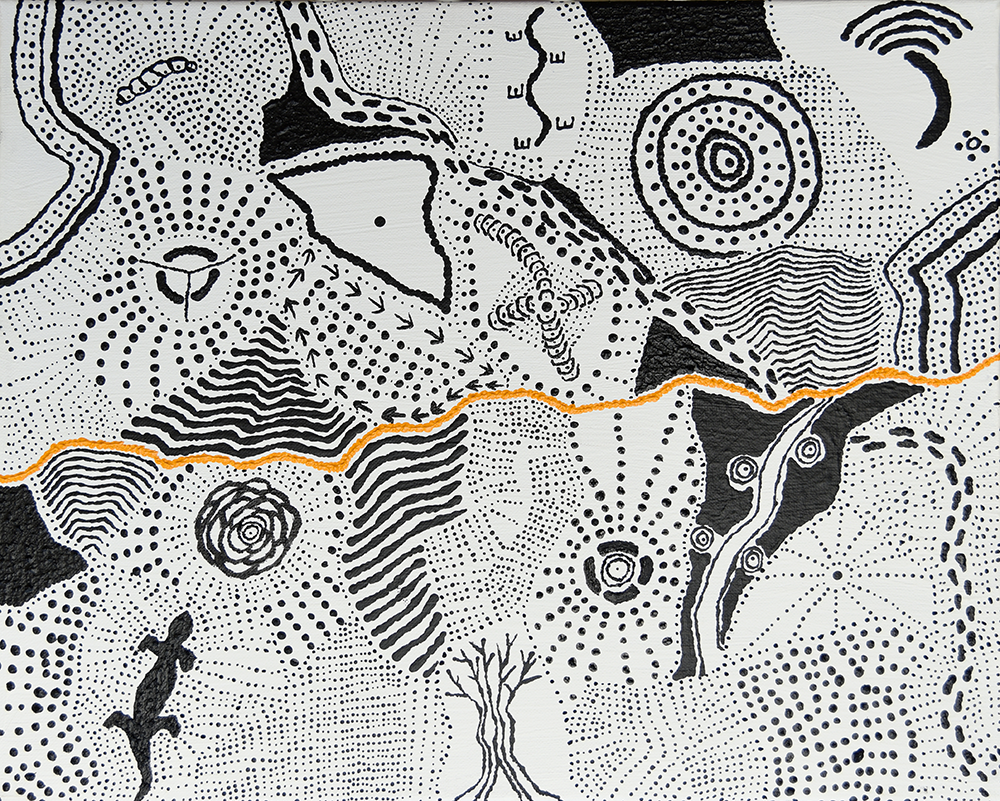

This piece explores a black and white cosmology, one which sees humans as the centre of the world and God as being only interested in them. It allows no room for those who are not white, human or productive and sees the Christian metanarrative only in these terms. It is one of three pieces in a series exploring the changing cosmology influencing the fading of a traditional understanding of the white Christian narrative.

This is a study for the larger An Australian Landscape - Canvas As Country. It reflects my personal story and includes ideas and symbols of personal importance alongside those of traditional life.

This is the second pice in the series. It introduces nature or creation as an equal in the ongoing story of creation through evolution towards wholeness. It understands that creation is unfinished in an ever expanding universe and that humanity's future is connected directly to the way we live in mutual respect with it.

We are in the process of a discussion about how to recognise indigenous Australians in the constitution. This piece suggests that only when deep dialogue occurs between equals resulting in true sovereignty and a treaty that recognises such will we have recognition.

The piece uses red to signify the bloody history of our country, the black lines as the fences and policies we have used to further that history, the black and white squares as the way we view our selves in opposition.

The tentative yellow lines and the meeting place reminds us that we have only just begun and that this process is fragile and can collapse at anytime.

This painting aims to capture the explosion begun in the far distant past and expanding into the far distant future. It explores land, water, nature slowly becoming, and becoming, and becoming.

There is no evidence of humans in this painting because we were late to arrive and will soon pass and the world will going becoming without us.

William Ricketts (1898–1993) was an Australian potter and sculptor who believed that all of life is one.

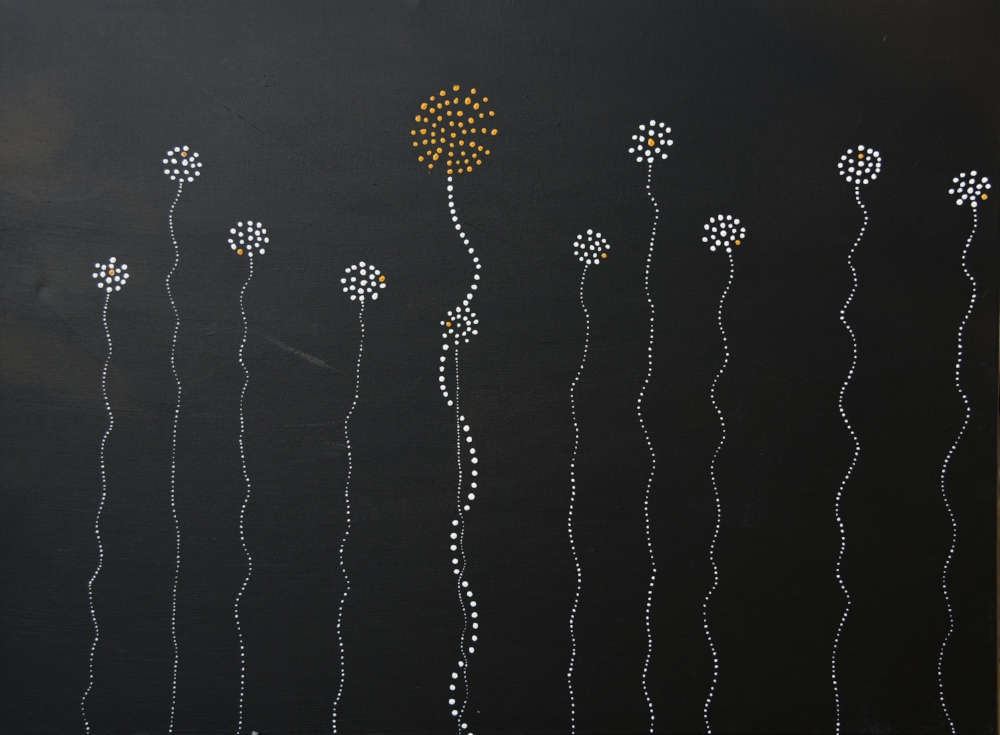

This painting of a simple dandelion (white) containing the essence of all creation (yellow dot) reflects, "the power of his vision of a modern Australia that embraces Aboriginal spirituality and respect for the natural world was his general message throughout his artworks."

A little introspective piece by God, after she knocked off work at the end of the first week of creation happy with the humble beginnings she had made on a project, which promised to be of an infinite nature.

I have used a discarded commercial canvas rescued fro an Op Shop, which had those words stencilled on it.

Somewhere Beyond Alice explores the interaction between the ancient and modern.

The elders of the McDonnell Ranges tower above the impermanence of modern life; a bitumen road and a burnt out car.

Artwork by Glenn Loughrey can be viewed the Murnong Gallery for Aboriginal Art. The Gallery was opened on 19 March 2022.

It is located at St Oswald’s Anglican Church Glen Iris, Melbourne and functions as a social enterprise at St Oswald’s. Churches, such as St. Oswald’s, are now working much harder to learn the truth of our Aboriginal history, and as a parish, St Oswald’s is delighted to be a supporter of the Gallery and its ambitions.